"I guess I'll be able to handle it when I'm a senior," one of my freshman students said, talking about the thesis she'd have to complete before graduating. "But for now it totally freaks me out." This student held a reasonable assumption that we all cling to: we'll outgrow our fears.

Hate to break it to you, but we do not outgrow our fears. (Just ask my grandma, who still hates the dark.) Fears themselves don't "go away" as we get older. What changes is our ability to manage those fears, and other strong emotions. The 20s are a key time for that development.

OK, we're going to get into brain science so get ready. (Do not fall asleep on me, people!)

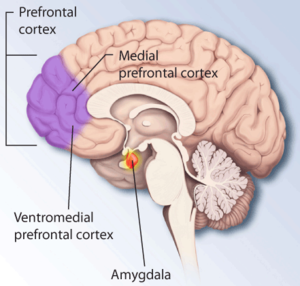

During puberty, the area of the brain that creates emotions - the limbic system, including the amygdala - grows rapidly. This causes emotion overload, with strong feelings popping out left and right. I think of it as a field of fireworks that has accidentally caught fire, causing the fireworks to shoot off randomly and in all directions.

That's why your feelings were so intense during adolescence, and why they changed so frequently - because your brain was churning out emotions the way the Duggars churn out kids.

If there were some way to control the surges of emotions - if we could, say, put a protective barrier over the blazing fireworks - then it wouldn't be too bad. And eventually, as we get older, we are able to do just this. But not for a while.

The part of the brain that controls emotions - the prefrontal cortex - is still developing into at least the mid-20s. In the early and mid-20s, nerve cells that we don't use die off. This makes our prefrontal cortex more efficient at controlling emotions. In addition, insulation (myelin) is accumulating around the nerve cells in that area of the brain, making the neural impulses faster. This insulation building may continue into the 30s.

In other words, we're still a bit unhinged in our 20s.

“The prefrontal part is the part that allows you to control your impulses, come up with a long-range strategy, answer the question ‘What am I going to do with my life?’" said the lead researcher, Jay Giedd, in the New York Times article What Is It About 20-Somethings. “That weighing of the future keeps changing into the 20s and 30s.”

So what's this mean for you? Well, you're not quite your adolescent self any more (thank goodness). But it also means that you do have a lot of "growing up" left to do.

Not "growing up" in the sense of getting rid of fear and the other emotions that block us - an emotionless life would be awful - but in the sense of handling them. That's what psychologists call emotion regulation, and it's a process we begin in the toddler years. (Not so successfully, I might add, as the frazzled mother of a 2-year-old.)

So, as a twentysomething, what can you do?

- Accept that your emotions are going to overpower you sometimes (often?!). Especially so-called negative emotions, like being afraid and feeling hurt. You literally can't help it. Your brain isn't equipped to override these emotions efficiently yet. When you feel afraid or sad or angry, just say to yourself "Oh sheesh, there goes my out-of-control amygdala again." You can even say it out loud. But only if you're looking to shed some friends.

- Use this knowledge to step back and let the emotion flow past you, whenever you can. You now know that emotional control isn't yet your strong suit, developmentally speaking. So choose to not let the emotions get the best of you. Emotions last only as long as we allow them to last. In her book My Stroke of Insight, neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor writes "there are certain limbic system (emotional) programs that can be triggered automatically, it takes less than 90 seconds for one of these programs to be triggered, surge through our body, and then be completely flushed out of our blood stream." If we keep thinking about whatever triggered the emotion - like fear that we'll let our parents down if we choose to pursue art instead of law - then our bodies continue to feel a flood of chemicals that cause the emotion. If we choose to think differently, the emotion passes. That's where #3 comes in.

- Come up with strategies to deal with fear and other strong emotions. Not thinking about fear and anger and sadness sounds great, but how do you do it? Strategically, that's how. You can override your brain's immaturity, if you have a plan in place. Since I've already bludgeoned you with neuroscience today, though, I'm going to end class here. In our next lecture this is where we'll pick up - with strategies that help us regulate emotions, especially that naughtiest one of all: fear.

In the meantime, your homework is to write about how your emotions have changed since your teen years. Do they feel different now, or do you just manage them differently?

Brain structures involved in dealing with fear and other strong emotions. The amygdala is a key part of the limbic system. If you're still reading, you might note that this is the most serious caption I've written on this blog. Go me! (Photo credit: Wikipedia)